|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

|

News | Sport | TV | Radio | Education | TV Licenses | Contact Us |

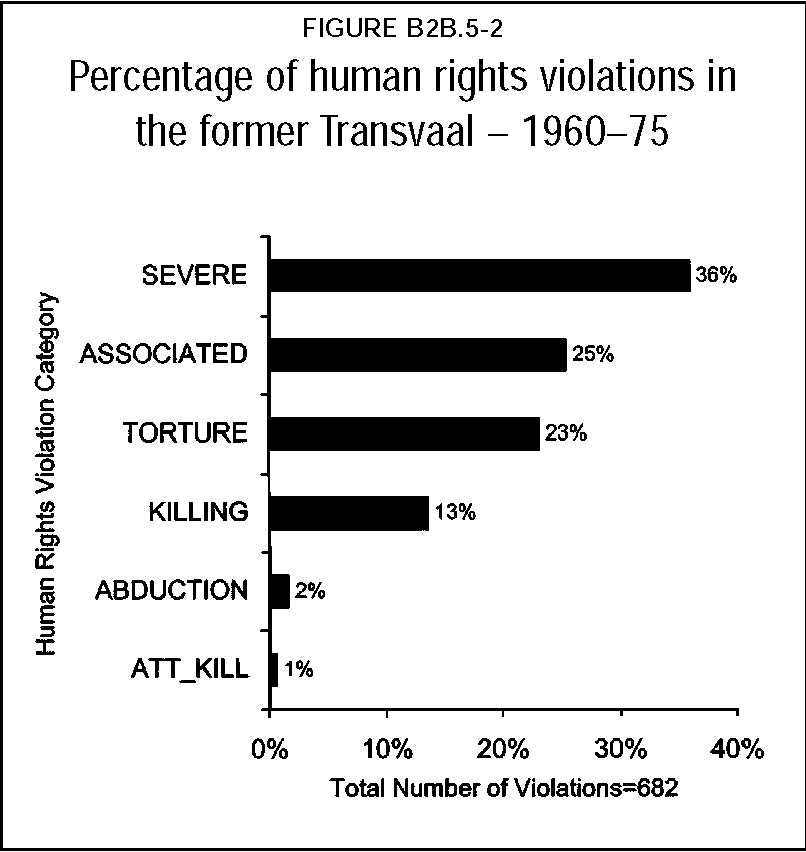

TRC Final ReportPage Number (Original) 533 Paragraph Numbers 22 to 31 Volume 3 Chapter 6 Subsection 4 Killings22 Although the shootings at Sharpville caused an international outcry against apartheid and precipitated the formation of underground armed opposition groups, it did not trigger the kind of widespread public protests and open street conflict that were occurred in subsequent decades. The violence of the police reaction to the pass protests and restrictions imposed on political activity effectively curtailed any large-scale public political protest until the 1970s. Hence, the level of killing violations during this period is relatively low (the fourth most significant category of all human rights violations, after severe ill treatment, torture and associated violations) Where perpetrators of killings are identified by victims, the overwhelming majority name members of the SAP.  23 The Sharpville shootings were an ominous foreshadowing of the widespread use of lethal force by the SAP, which characterised later street protests. Sharpville massacre24 On Monday 21 March 1960, sixty-nine people died when police opened fire on approximately 300 marchers protesting against the pass laws at Sharpville in the Transvaal. Conflict erupted in Langa, Cape Town, almost simultaneously, leaving two people dead and more than fifty injured. In the ensuing days violence spread to Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Port Elizabeth, East London and Bloemfontein. 25 The march was organised and planned by the PAC. In its verbal submission to the Commission, the PAC outlined the history of the organisation’s anti-pass campaign and emphasised the commitment of its organisers to peaceful protest. The March 1960 protest action against the pass laws built on the success of the PAC Status Campaign which focused on the idea of mental liberation. PAC representatives told the Commission that it was “an absolutely non-violent campaign”.1 PAC leader Robert Sobukwe, reportedly announced before the march that “we are ready to die for our cause but we are not ready to kill”. Before the march, a letter was sent to the commissioner of police, Major General Rademeyer “explaining fully the peaceful nature of the campaign”. A media conference was held pledging that the campaign would be conducted in a peaceful manner. Despite these assurances, the protest was met with a heavy-handed response from the state and the security forces. 26 Many PAC leaders were arrested. PAC representatives told the Commission that, because the campaign was conducted on the principle of no bail, no defence and no fine, PAC leaders and members were convicted and sentenced to periods of imprisonment. 27 The Sharpville shootings radically shifted the nature of political resistance in South Africa. They signalled an end to the era of non-violent struggle and ushered in a period of armed struggle. The shootings also provoked strong condemnation from the international community. The policy of apartheid came under the spotlight and was debated for the first time by the United Nations Security Council. March 21 was formally declared the international day for the struggle against racism. 28 While the carrying of pass books was a source of widespread protest, evidence before the Commission points to a degree of coercion of non-politicised Sharpville residents who were pressurised into participating in the anti-pass protest, although most residents were prepared to support the public protest. Although Ms Korisatsana Elizabeth Mabona [JB00793/03VT] and Mr Ntele David Ramokhoase [JB00902/03VT], neither of whom belonged to any political organisation, were forcibly prevented from going to work on the day of the march, they told the Commission that they were unequivocal in their rejection of the pass system. Mr Ramokhoase told the Commission that the dompas was “just a misery”. 29 On Thursday 17 March a pamphlet was circulated in Vereeniging urging people to stay away from work on the following Monday. During the following days, bus drivers were approached and urged not to go to work. One bus driver claimed that PAC activists collected them from their homes in the middle of the night and only released them after sunrise. Telephone wires linking Sharpville with Vereeniging were cut on the Sunday evening before the march. At Sharpville’s Seeiso Street bus terminal, near the new police station, PAC organisers told commuters they should not go to work. 1 PAC submission to the Commission, August 1996.30 By 10h00, a large crowd had formed in the centre of Sharpville. Despite tension early on Monday morning, people at the gathering in Sharpville all described it as a happy occasion. Ms Elizabeth Mabona whose husband, Mr Jacob Ramokoena, was killed later that day told the Commission: At the police station we sat down, we were singing hymns, you know it was just a jolly atmosphere. We were singing these hymns as Christians because we were just rejoicing. And we didn’t know what will follow thereafter. We were just joyous because we thought that same afternoon we would get a message. Everybody was taking his feelings out. 31 Large groups of people had also gathered in Bophelong and Boipatong townships. They joined a march, 4 000-strong, in a procession to Vanderbijlpark police station. In Evaton 20 000 people assembled outside the police station. The crowd in Vanderbijlpark was immediately dispersed by a police baton charge and in Evaton with low-flying Sabre jets. In Vanderbijlpark, one man was killed when police fired on a group of men who, they alleged, were stoning them. Ms Elizabeth Mabona said that in Sharpville, however, the aircraft failed to intimidate people: We spent that whole time at the police station until the jets arrived. We didn't mind. The sirens went off and then we just ignored them. |